How The Fur Trade Caused The Extention Of Many Species Of Animal During The Old West

The fur trade was a vast commercial enterprise across the wild, forested area of what is now Canada. It was at its peak for about 250 years, from the early on 17th to the mid-19th centuries. It was sustained primarily by the trapping of beavers to satisfy the European need for felt hats. The intensely competitive trade opened the continent to exploration and settlement. Information technology financed missionary piece of work, established social, economic and colonial relationships between Europeans and Indigenous people, and played a determinative role in the creation and development of Canada.(This is the full-length entry nigh the fur trade. For a plain-linguistic communication summary, delight see Fur Merchandise in Canada (Plain Language Summary).)

Fishing, Furs and Christianity: Early Euro-Indigenous Relations (1608–63)

The fur trade began as an adjunct to the fishing industry. Early in the 16th century, fishermen from northwest Europe were taking rich catches of cod on the M Banks off Newfoundland and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Drying their fish onshore took several weeks. During that time, good relations had to be maintained with Indigenous people, who were eager to obtain metallic and cloth goods from the Europeans. What they had to offer in commutation were furs and fresh meat. The fishermen institute an eager and profitable market in Europe for the furs.

When the broad-brimmed felt hat came into fashion later on in the 16th century, the demand for beaver pelts increased tremendously. The best material for chapeau felt was the soft underfur of the beaver. Its strands have tiny barbs that make them mat together tightly.

To exploit the merchandise more effectively, the first French traders established permanent shore bases in Acadia, a post at Tadoussac. They also founded a base of operations at Quebec in 1608. The following year, the Dutch began trading up the Hudson River. In 1614, they established permanent trading posts at Manhattan and upriver at Orange (now Albany, New York). This activity marked the beginning of an intense rivalry between the ii commercial empires of the Dutch and the French. It besides involved their respective Indigenous allies, the Huron-Wendat and the Haudenosaunee, both of whom were supplied with guns by their European allies. (Meet also: Indigenous-French Relations.)

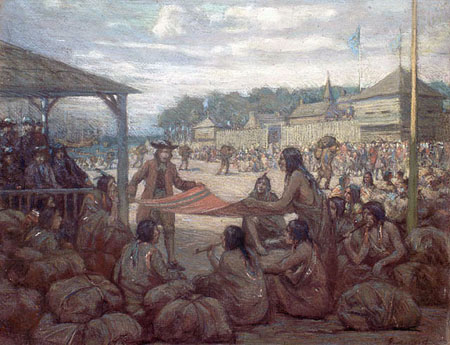

Indigenous peoples were of import partners in this growing fur merchandise economic system. From roughly 1600 to 1650, the French forged alliances of kinship and trade with the Huron-Wendat, Algonquin and Innu. These peoples helped the French collect and process beaver furs and distribute them to other Indigenous groups throughout their vast trade network, which was established well before the arrival of Europeans. The fur trade provided Indigenous peoples with European goods that they could use for gift-giving ceremonies, to meliorate their social status and to go to war. The French forged war machine alliances with their Indigenous allies in order to maintain adept trade and social relations. In the 17th century, the French fought confronting the Haudenosaunee in the struggle for control over resources. This was known as the Beaver Wars or the French and Iroquois Wars.

During the start half of the 17th century, the number of traders flooding into the St. Lawrence River region, and cutthroat competition amongst them, greatly reduced profits. In an attempt to impose lodge, the French Crown granted monopolies of the merchandise to certain individuals. In return, the monopoly holders had to maintain French claims to the new lands and assistance in the attempts of the Roman Catholic Church to convert Indigenous people to Christianity.

In 1627, Cardinal Richelieu, commencement minister of Louis 13, organized the Compagnie des Cent-Associés to put French territorial claims and the missionary drive on a firmer basis. Four Récollets missionaries were sent to Québec in 1615. They were followed in 1625 by the first members of the powerful Society of Jesus (Jesuits). A mission base, Ste Marie Amongst the Hurons, was established amid the Huron-Wendat nigh Georgian Bay. Nevertheless, the Huron-Wendat were more interested in the merchandise goods of the French than in their religion. And it was fur-trade profits that sustained the missionaries and allowed the company to send hundreds of settlers to the colony. In 1642, Ville-Marie (now Montreal) was founded as a mission centre. In 1645, the company ceded control of the fur merchandise and the colony'southward administration to the colonists. (See besides: Communauté des habitants.) Unfortunately, they proved to be inept administrators, and fur-trade returns fluctuated wildly. Finally, afterwards a drastic appeal by the colonial authorities to Louis Xiv, the Crown took over the colony in 1663.

French Control and French Profits (1663–1700)

The main staple of the merchandise was nonetheless beaver pelts for the hat manufacture. The Ministry of Marine, responsible for colonial affairs, leased iii overseas enterprises — the Due west Indies plantation trade, the African slave trade, and the marketing of Canadian beaver and moose hides — to the newly formed Compagnie des Indes occidentales. In reality, information technology was a crown corporation. All permanent residents of New France were permitted to merchandise for furs with Ethnic people. Even so, they had to sell the beaver and moose hides to the company at prices fixed by the Ministry of Marine. All other furs were traded on the complimentary market. Thus, the trade was not a monopoly, simply the police force of supply and demand had been suspended for beaver and moose hides.

Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the French government minister of marine, hoped the Canadian economy would diversify to provide French industry with raw materials. These would include timber, minerals and foodstuffs for the West Indies plantations. Thousands of emigrants were shipped to Canada at the Crown's expense to bring the state into product. (Encounter also: Filles du Roy.)

Colbert discovered that a sizable proportion of the immature men did not remain on the land. Instead, they disappeared for years at a fourth dimension to trade with Indigenous people in afar villages. (See besides: Coureurs de bois.) The main reasons for this phenomenon were the assured profits in the trade and the imbalance of the sexes in the colony. It was so nifty that until about 1710, only almost one man in 7 could promise to find a wife — a necessity on a subcontract. In the interior, however, the traders quickly formed alliances with Indigenous women. Their economical skills helped the French adapt to wilderness life. Women made wear and moccasins and helped to supply the fur trade posts. (See also: Clothing During the Colonial Period.) About importantly, they fostered kinship ties betwixt Europeans and Ethnic peoples. This linked the two groups in more than but trade and economy.

Past 1681, Colbert was forced to acknowledge the pull of the fur merchandise. He inaugurated the congé organization. Each twelvemonth, up to 25 congés (licences to merchandise) were issued by the governor. Each congé allowed 3 men with i canoe to trade in the W. It was hoped that the Canadians would wait their turn for a congé, thus leaving the colony just 75 men short each year. But the new system did little to reduce the number of men away from the settlements (most of them illegally). The amount of beaver pelts pouring into Montreal continued to increase dramatically. By the 1690s, the Domaine de fifty'Occident (Company of the Farm) was complaining of a huge overabundance. (The Domaine de 50'Occident had been obliged to take over the beaver trade in 1674 from the defunct Compagnie des Indes occidentales.) In 1696, in desperation, the minister of marine suspended the beaver trade. He also gave orders to finish the issuing of congés and to abandon all the French posts in the West, except Saint-Louis-des-Illinois.

War and Rivalry: France, England and Ethnic Peoples (1701–15)

The lodge to abandon the Western trading posts (to wearisome the migration of men into the beaver trade, and to reduce the overabundance of pelts) was given while England and France were at state of war. The Canadians were engaged in a desperate struggle with the English colonies and their Haudenosaunee allies. (See also: Beaver Wars.) The governor and intendant (French ambassador) in Quebec protested vigorously. They declared that to abandon the posts in the West meant abandoning their Indigenous allies. Past the latter half of the 17th century, these too included the Saulteaux (Ojibwa), Potawatomi and Choctaw. The French feared that these peoples would become allies of the English. If that happened, New France would be doomed.

In addition, the English had been established at posts on the sub-Arctic coast of Hudson Bay since 1670. (See as well: Hudson's Bay Company (HBC).) The western posts were essential to fend off that contest. The Canadian Compagnie du Nord had been founded in 1682 to challenge the HBC on its own basis, but it was a failure. The minister of marine was obliged to rescind his desperate orders. The beaver trade resumed in spite of the over-supply, for purely political reasons.

In 1700, on the eve of new hostilities, Louis Fourteen ordered the establishment of the new colony of Louisiana on the lower Mississippi River, plus settlements in the Illinois country and a garrisoned mail at Detroit. The aim was to hem in the English colonies between the Allegheny Mountains and the Atlantic. This imperialist policy depended on the back up of the Beginning Nations. In 1701, the French and their allies reached a truce with the Haudenosaunee, known as the Great Peace of Montreal. This effectively concluded the Beaver Wars over the fur trade. By that time, however, the wars had already resulted in the permanent dispersal or destruction of several First Nations in the Eastern Woodlands, including the Huron-Wendat. (See also: Hurons-Wendat of Wendake.)

Voyageurs

In 1715, it was discovered that rodents and insects had consumed the glut of beaver fur in French warehouses. The market immediately revived. Equally an detail on the remainder sheet of French external trade, furs were minuscule. Their share was also shrinking proportionately as trade in tropical produce and manufactured appurtenances increased. However, the fur trade was the backbone of the Canadian economy.

Dissimilar the HBC, with its monolithic structure staffed by paid servants, the fur trade in New France was carried on into the early on 18th century by scores of small partnerships. As costs rose with distance, the trade came to be controlled by a modest number of bourgeois. They hired hundreds of wage-earning voyageurs. Most companies consisted of three or 4 men who obtained from the regime a lease at a specific post for three years. All members of a company shared profits or losses proportional to the capital invested. Trade goods were commonly obtained on credit, at 30 per cent interest, from a small-scale number of Montreal merchants. They also marketed the furs through their agents in France. The voyageurs' wages varied from 200 to 500 livres if they wintered in the West. For those who paddled the canoes due west in the leap and returned with the autumn convoy, the usual wage was 100–200 livres plus their keep (near double what a labourer or artisan would earn in the colony).

Westward Expansion (1715–79)

Between 1715 and the Seven Years' War (1756–63), the fur merchandise expanded profoundly and served a multifariousness of purposes — economic, political and scientific. Educated Frenchmen were keenly interested in scientific research. Government members, eager to discover the extent of North America, wished a Frenchman to be the kickoff to find an overland road to the Western sea. (See also: Northwest Passage.) Commissions were granted to senior Canadian officers such equally Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye to discover that route. They were given command of vast Western regions (some of which overlapped territory claimed by the British), with sole right to the fur trade. Out of their profits they had to pay the expenses of maintaining their posts and sending exploration parties westward along the Missouri and Saskatchewan rivers.

The Crown thereby made the fur merchandise pay the costs of its pursuit of science. It also maintained command over both its subjects in the wilderness and its alliances with the Starting time Nations in social club to exclude the English. Past 1756, when war with England put a stop to exploration, the French had reached the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. Warfare between the Blackfoot and Cree prevented further advances.

Hudson's Bay Visitor and Other English Traders

Throughout this period, there was groovy contest between the French Canadian traders and the HBC. The Canadians took the king of beasts's share of the merchandise. They had many advantages: they controlled the main waterways throughout the West; they had a sure supply of the birch bark needed for canoes (something the Anglo-Americans and the HBC men both lacked); many of their trade goods were preferred past the Indigenous people; and they had skillful relations with the Outset Nations, with whom they had developed extensive kinship ties. Attempts by the English of the Thirteen American Colonies to obtain more country for settlement angered the Indigenous people. The French did non covet Indigenous lands but were determined to deny them to the English language.

The HBC traders made no real try to push their trade inland. Instead, they waited in their posts for Indigenous people to come to them. The First Nations were acute enough to play the English and French against each other by trading with both. The French dared not try to prevent Ethnic people from taking some furs to the Bay, but fabricated sure to obtain the choice furs, leaving only the bulky, poor-quality ones to their rivals.

In the St. Lawrence region, New York and Pennsylvania traders made little effort to compete with the Canadians. Instead, they purchased furs clandestinely from the Montreal merchants. In this fashion the Canadians obtained a skilful supply of strouds (coarse English woollen fabric), a favourite English trade detail. The illicit trade betwixt Montreal and Albany as well removed whatsoever incentive the New York traders might have had to compete with the Canadians in the W.

When the Seven Years' War began, the fur merchandise continued out of Montreal. The Showtime Nations people had to be kept supplied, but the volume of exported furs steadily declined. Within a year of the French capitulation of Montreal in September 1760 and the subsequent conquest of New France, the trade began to revive. It was largely supported past British capital and Canadian labour.

Rise of the North West Visitor (1779–1810)

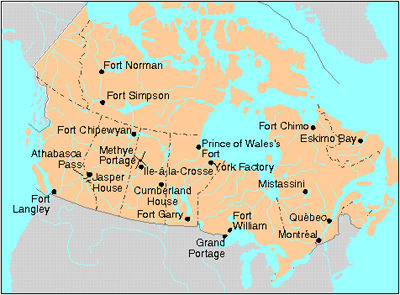

At the fourth dimension of the conquest of New French republic, over the period 1759–60, ii systems dominated the commercial fur trade of the northern half of the continent: the St. Lawrence- Great Lakes organization, based in Montreal and extending to the upper reaches of the Mississippi River and its major northern tributaries, every bit well as to the prairies and the southern portion of the Canadian Shield; and the Rupert'south State system, which covered the whole region draining into Hudson Bay and James Bay.

The St Lawrence-Great Lakes system, adult past the French, had come up to be served by the en dérouine (itinerant peddling) blueprint of trade. This type of trade was dominated by many small partnerships. It was conducted by parties of a few men sent out to practise business with the Showtime Nations in their own territory. The Rupert's Land trading organization, by contrast, had not evolved in the same style. In 1760, the HBC'southward employees even so followed the exercise of remaining in their coastal "factories" (major trading posts), awaiting the inflow of Ethnic people to trade.

After the Conquest, Anglo-Americans (Yankees, or Bastonnais), and English and Highland Scots merchants supplanted the Canadian bourgeois and the agents of French merchants in Montreal. The new "pedlars" forged a new commercial link with London. The resulting upsurge in activeness in Montreal disturbed the HBC's "slumber by the frozen sea." The success of its new rivals forced the visitor to alter its declension-factory trading policy. In 1774, the HBC penetrated inland from the Bay to found Cumberland House, close to the Saskatchewan River. For their part, the pedlars learned that co-operation among themselves, rather than competition, was the route to commercial success.

The resulting North W Company (NWC) rose rapidly to a position of authority past gaining a de facto monopoly of the trade in the fur-rich area around Lake Athabasca. (See too: The Northward West Company, 1779–1821.) Staple fur (beaver) and fancy furs (mink, marten, fisher, etc.), unsurpassed in quality and number, bodacious handsome profits. They did so fifty-fifty in spite of the high costs of the necessarily labour-intensive transportation system, the canoe brigade. The annual dash of brigades from Fort Chipewyan to G Portage (later to Fort William) on Lake Superior created much of the romantic image of the fur merchandise. To maintain its Athabasca monopoly the NWC competed, at a loss if necessary, with its opponents on the Saskatchewan River, effectually Lake Winnipeg and due north of the Great Lakes. On the North Saskatchewan River, the rival companies leapfrogged westward by each other's posts in an endeavor to gain a commercial advantage with Start Nations.

In all regions, pocket-sized trading parties journeyed with supplies of trade goods to waylay Indigenous people travelling to rivals' posts. When necessary, they would force them to merchandise. In this contest, the HBC appeared disadvantaged in spite of having a major shipment postal service, York Factory, on Hudson Bay. It was much closer to the fur-gathering areas than was the NWC'southward trans-shipment betoken of Montreal.

The HBC lacked personnel and equipment equal to the tasks of inland travel and trade. Non until the 1790s did the HBC evolve the York Gunkhole brigade as an answer to its rival's canot de maître and canot du nord. Even so, improved equipment and personnel were not sufficient to turn the commercial tide in the visitor'due south favour.

Montreal agents, such as Simon "The Marquis" McTavish and his nephew and successor William McGillivray, shrewdly directed the NWC's affairs. Nevertheless, much of the company's success was due to the enthusiasm of its officers and employees (engagés). Wintering partners participated in decision making and enjoyed the profits of the trade. Dissimilar the HBC, the NWC's credence of intermarriage between traders and Ethnic wives resulted in a certain stability. The mixed-descent children of these "country marriages" — known as the Métis people — established themselves as traders, buffalo hunters and suppliers to the NWC. By the early 19th century, sizeable Métis populations existed around trading posts and especially in the Red River Colony.

In 1789, Alexander Mackenzie carried the NWC'south flag to the Arctic Body of water. In 1793, he reached the Pacific Ocean overland. (Run across also: The Explorations of Alexander Mackenzie.) Later explorers such as Simon Fraser and David Thompson opened up the fur lands west of the Rocky Mountains. The signing of Jay's Treaty in 1794 ended the southwest trade. A new rival, the XY Company, appeared in 1798. Just the NWC met its challenge and in 1804 it absorbed this upstart.

Hudson's Bay Company Triumphs (1810–21)

Information technology was the revitalization of the HBC offset in 1810 that ultimately defeated the NWC. That year, the Earl of Selkirk decided to institute a settlement in HBC territory. He purchased sufficient stock to place four friends on the HBC's seven-man governing commission. These men, new to the company, emphasized efficiency in the trading process to reduce costs and turn from loss to profit. This success led the company to attempt to invade the Athabasca state in 1815. Poor planning by the trek's leader and the NWC'south influence with the Indigenous people in the region caused as many as 15 men to die of starvation. Only the HBC was undaunted. Information technology returned a few months subsequently and successfully challenged the NWC monopoly.

The governing committee gave Selkirk'due south Red River Colony assistance and co-functioning, although officers in the region were unenthusiastic. The NWC saw the settlers equally supporters of their newly revitalized commercial rival. The NWC convinced the local Métis, who had settled the region, that their lands were threatened. Commercial disharmonize erupted in violence when the colony's governor and some 20 other settlers and HBC servants were killed in the 7 Oaks incident on xix June 1816. The Métis lost just one man.

Such occurrences led the British government to demand that the competing fur companies resolve their differences. To this end, the regime passed legislation enabling it to offer an exclusive licence to trade for 21 years in those areas of British North America beyond settlement and outside Rupert's State. In 1821, the ii companies created the "Human activity Poll." This document outlined the terms of a coalition between them. It detailed the sharing of the profits of the trade between the shareholders and private officers in the field. It also explained their relationship in the management of the trade. It was in this manner, and in the sharing of profits, that elements of the NWC survived in the new HBC. All the same, what was a coalition in proper noun became assimilation by the HBC. In 1824, the lath of management was eliminated. A majority of officers working for the HBC after 1821 were former Nor'Westers.

Simpson Consolidates the HBC's Fur Trade Empire (1821–lxx)

Commercial agreements between the two separate companies and the support given by authorities legislation and annunciation could not hide the NWC'southward defeat. The victorious HBC once once more sought to increase its efficiency. Nether the direction of Governor George Simpson, known as the "Little Emperor," the HBC accomplished undreamed-of profits. But such profits required a constant monitoring of costs and a abiding search for savings, equally well as a policy of sharp competition with rivals in edge areas. Through the company's policies and the deportment of its personnel, the inhabitants of the onetime North-West were exposed to the influence of changes wrought in Britain past the Industrial Revolution, including the creation of workforces dependent on company employment.

Simpson conspicuously saw the importance of providing support to Indigenous people's hunting and trapping. These activities supplied the furs that sustained the HBC'south fortunes. In times of arduousness, the company offered medical services and sufficient supplies and provisions for the trapper and his family unit to survive. Yet in systematizing these services, Simpson'southward policies led Ethnic people into an increasingly dependent human relationship with the HBC. The Plains Ethnic peoples, could be independent of the visitor'southward services while the buffalo hunt was still viable. But for others, the new reality was increasingly economic dependence.

Simpson's reforms allowed HBC expansion along the Pacific declension, northward to the Arctic, and into the interior of Labrador, which had been largely ignored until then. Such a vast fur domain attracted rivals. Simpson'southward fundamental strategy was to meet competition in the frontier areas to preserve the merchandise of the interior for the HBC. On the Pacific coast, he reached an agreement with the Russian Fur Visitor that permitted the HBC to pursue the maritime trade and successfully challenge the pre-eminence of the Americans. South and east of the Columbia River, he encouraged expeditions to trap the region make clean in a "scorched-earth" policy. This left no animals to attract American "mount men" or trappers. In the Great Lakes surface area, he licensed small traders to comport competition to the territory of the American Fur Visitor, eventually causing it to abandon the field for an almanac payment of £300.

Farther east, the opponents were more difficult to dislodge. The King's Posts, a series of trading posts north of the St. Lawrence originally belonging to the French male monarch, had been granted in 1822 to a Mr. Goudie of Quebec City. Forth the Ottawa River, lumbering provided bases for competition to arise. Yet the HBC vigorously pursued its competitors in all the frontier areas. It sustained its monopoly of the trade in Rupert'south Land and in the licensed territories to the northward and west. In the 1830s, when silk replaced felt every bit the favoured raw material in the manufacture of hats and beaver lost its value as a staple fur, the company maintained a profitable trade emphasizing fancy fur. Instead, it was settlement, not commercial rivals, that presented the biggest challenge to the HBC.

Challenge of Settlement

Westward of the Rocky Mountains, American settlers succeeded where their predecessors, the mountain men and the ships' captains, had failed. Every bit a result of the Oregon Treaty of 1846, the HBC retreated north of the 49th parallel of latitude. To the eastward, at the Red River colony, the HBC met the challenge of costless traders by charging Pierre-Guillaume Sayer and three other Métis in 1849 with violation of the HBC monopoly. (Run across besides: Sayer Trial.) Although the company won a legal victory in the courtroom, the community believed that the costless traders had been exonerated. In Lower Canada, the company acquired the lease for the Rex's Posts in 1832. Nevertheless, the northward march of lumbermen signalled the lessening importance of the fur trade in this region. Simpson countered brilliantly by making his visitor an of import supplier of goods needed by the lumber crews.

When the geographical isolation of the West was breached in the 1840s, forces other than the fur interests became involved in opening the "Great Lone Country." Catholic and Anglican missionaries who had appeared earlier now penetrated to the heart of the continent. They were followed by adventurers and regime expeditions seeking resources other than fur, such every bit timber, territory, and scientific knowledge. (See also: Palliser Expedition.) Simpson's death in 1860 and the sale in 1863 of the HBC to the International Financial Society, a British investment group, marked the beginning of the end of the historic fur trade.

The Stop of the Fur Merchandise

In 1870, the HBC's vast territory in the West was transferred to Canada. The adjacent yr, the federal authorities began signing treaties with the Indigenous peoples of the expanse. (Encounter also: Numbered Treaties.) The government acquired title to those traditional lands and opened them upwards to settlement and development. What had been a trickle of settlers coming from Ontario now became a overflowing. As settlement spread n and west, the HBC and rival gratuitous traders intensified the northward push of the trade, and somewhen established enduring trading contacts with the Inuit. Fur traders moved into the chill territories of whalers, who had abandoned their posts equally the whaling economy declined. From 1912 to the early 1930s, the HBC established a series of trading posts in the arctic.

In the confront of contest and the presence of the Canadian government, the HBC reduced the support services that had been a office of its trading relationship with the First Nations. These services had buffered Indigenous people against the swings of fur-market demands in Western Europe. In the 20th century, fortunes in the fur merchandise came to reverberate the swings of the market and the advent of fur farming. (See besides: Fur Manufacture). Increasingly, Indigenous people looked to the missions and even more to the government for support in times of adversity. This shift culminated in the granting of family allowance, schooling and pensions afterward the 2nd World State of war. It also marked the end of the historic fur trade. Fur trapping continues equally a cash crop in frontier areas, but equally a way of life it is bars to a few northern areas.

Significance

Historically, the fur trade played a singular function in the development of Canada. It provided the motive for the exploration of much of the state. The trade remained the economic foundation of Western Canada until about 1870. The fur trade also adamant the relatively peaceful patterns of Indigenous-European relations in Canada. A central social attribute of this economic enterprise was extensive intermarriage betwixt traders and Indigenous women. This gave rise to an indigenous fur-merchandise society that blended Indigenous and European customs and attitudes.

Source: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/fur-trade

Posted by: nelsonhistiamseent.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How The Fur Trade Caused The Extention Of Many Species Of Animal During The Old West"

Post a Comment